Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Godfather of America's Coin Renaissance

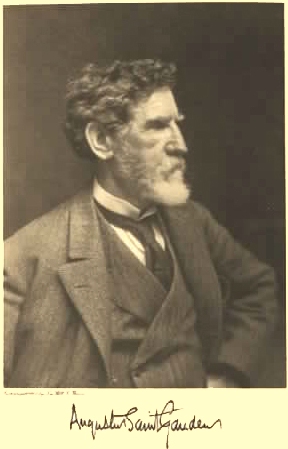

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) was the greatest American sculptor of the Beaux-Arts era. His internationally acclaimed statues and reliefs were compared favorably to those of elite European sculptors such as Rodin, and grace many of the world's most prestigious museums.

Some of the most famous of Saint-Gaudens's more than 200 works include the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial on Boston Common; the gilded equestrian statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman in Central Park; and his giant bas-relief of author Robert Louis Stevenson residing in St. Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland.

As famous as Saint-Gaudens is for both his monumental sculptures and medallions, his most-duplicated work is something most patrons of the arts have never seen: the 1907–1933 American “double eagle” gold coin.

ART OF THE AMERICAN CENTURY

The era between 1876 and 1917 in the United States saw the birth of the first distinctly American forms of art. Saint-Gaudens ("Gaud" pronounced like "gaudy"), and his contemporaries who trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris brought home a dynamic style of painting, sculpture, and architecture, sparking what was known as the "American Renaissance."

Sculpture became more compelling, capturing in bronze and marble the energy of an America that, its citizens felt, was taking its rightful place at the forefront of the community of nations. Instead of Roman gods and goddesses, the allegorical subjects of the American Renaissance represented ideas such as Progress and Liberty.

Saint-Gaudens was a master of capturing that energy in bronze. Whether it was displaying an inner strength, as exhibited by his Standing Lincoln monument in Chicago, or the active power of a subject caught in motion, as demonstrated by marching soldiers of his Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, his works displayed a dynamism that few others could match. This extended to his work on the $20 double eagle gold coin.

Influences On Saint-Gaudens's Coin Designs

Augustus Saint-Gaudens's career began in 1861 with his apprenticeship to a cameo cutter at the age of thirteen. He later used his cameo cutting skills to support himself in Europe while completing his formal education. His expertise in this medium led to his being one of the most sought-after cameo cutters by wealthy Americans touring Europe in the 1870s.

Cameo carving is by far the most difficult form of semiprecious gem cutting. It combines bold strokes with tiny, intricate details to produce a lifelike image in an ultra-high relief in a very small space. Saint-Gaudens carved countless hundreds of cameos between the ages of thirteen and twenty-five, to the point where he could carve a lion's head cameo without thinking.

This propensity for executing small works in very high relief carried through to his 1907 designs for the U.S. double eagle gold coin, which led to problems with the U.S. Mint and its resentful chief engraver, Charles Barber.

Europe and the École des Beaux-Arts

The greatest artistic influence in Augustus Saint-Gaudens's life was his education at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which was the epicenter of the revolution in art that would carry its name. Hundreds of artists and architects fought for a spot at the École each term. Only the best of the best were accepted. Those sculptors and architects that succeeded in surviving the punishing, non-stop workload of their education became masters in their field.

Saint-Gaudens was accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1868. He was only the second American sculptor to win admittance to the school, preceded by Howard Roberts in 1866. More American sculptors followed, eschewing the Neoclassical training of Rome for the fluid, vibrant style taught in Paris, and adapting it to capture uniquely American subjects in marble and bronze.

During the Franco-Prussian War, Saint-Gaudens left Paris for the safety of Rome. There, he cut cameos and sculpted replicas of famous Romans to support himself, while working on his first major statue, Hiawatha. Instead of referring to ancient Roman sculpture to improve his skills as were everyone around him, Saint-Gaudens turned to the more lifelike work of Renaissance masters for inspiration.

1907 Saint-Gaudens $20 Reverse

1907 Saint-Gaudens $20 Obverse

When he returned to the United States in 1875, he was well-grounded in both classical sculpture as well as the cutting edge of the Beaux-Arts movement. This synthesis can clearly be seen in both his traditional and allegorical works, where he imparts in his subjects not only a dignity in their pose, but also the sense of realistic movement in their clothing and hair.

These skills made the 1907 double eagle gold coin the most lifelike American coin to that date, later rivaled only by the 1916 Walking Liberty half dollar designed by his former assistant, Adolph Weinman.

It's Done When It's Done

Another trait of Saint-Gaudens throughout his career was his penchant for constantly reworking projects. This inability to let go of a project inevitably led to deadlines being missed by months or even years. He held the conviction that a sculptor is judged not only by his client, or even by the public, but by history. This is illustrated by his response to a complaint regarding the time one of his former students was taking on a monument.

"...[T]oo much time cannot be spent on a task that is to endure for centuries… You should consider yourself fortunate not to have fallen into the hands of a sculptor who would rush the commission through on time, regardless of the future, in order to get and make quickly the most money possible. A bad statue is an impertinence and an offense..."

Saint-Gaudens also had a problem with saying "no" to his patrons. This resulted on his working on a large number of commissions at once, which only magnified the time needed to complete a major project. This practice played a large part in his tribulations with the U.S. Mint regarding the redesign of America's most important gold coins.

NOTEWORTHY COMMISSIONS

The Shaw Memorial

Saint-Gaudens's most extreme and spectacular example of his philosophy of sculpting for the ages was the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial. By going far beyond the original scope of the commission, he created an astounding fourteen-foot by eleven-foot, three-dimensional panel that was widely regarded as the greatest public monument in America.

Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment Memorial. Image via Carptrash, Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

It also took him fourteen years to accomplish. The $15,000 commission was a fraction of what the memorial eventually cost, so Saint-Gaudens was required to take on other, profitable commissions to earn a living. The Shaw monument was finally unveiled in 1897 on Boston Common, near where Colonel Shaw and the African-American soldiers of his 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry marched to war 34 years earlier.

When Augusté Rodin saw the full-size replica of the Shaw on exhibit at the 1900 Paris Salon, he removed his hat and silently bowed before it. The worldwide acclaim of the Shaw established Augustus Saint-Gaudens's as one of the greatest sculptors in the world. As such, it could be said that it also validated his belief that vision and skill must take precedence over deadlines.

Amor Caritas

Amor Caritas (“Love and Charity”), also known as "Angel With Tablet," was one of Saint-Gaudens's favorite works. He took every opportunity to revisit the theme in commissions throughout his life.

Perhaps the most well-known version owes its existence to his friend, the painter John Singer Sargent. Sargent had a habit of stopping by Saint-Gaudens's studio to chat whenever the sculptor was working in Paris. On one of these visits, he asked if he could paint the “Angel With Tablet,” which he had always admired. Saint-Gaudens reworked the model from one meant for marble to a far more detailed one which he cast in bronze.

Image credit: Joanna Powell Colbert | Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), Manhattan

Standing 8'9" tall, it won a Grand Prize at the 1900 Paris Exposition (World's Fair). This was the angel that the French government purchased for the Luxembourg Museum in Paris (along with a series of medallions), making it Saint-Gaudens's first sale to a European museum. He adapted this version to a smaller size which became one of his most popular reproductions.

A comparison of Amor Caritas with Saint-Gaudens's “Winged Liberty” on the first prototypes of the 1907 double eagle show an unmistakable influence of the former on the latter.

Tensions With Charles Barber

Charles Barber was the sixth Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint, dating from his father William's death in 1879 to his own death in 1917. His career at the mint was founded on nepotism rather than skill, being hired as Assistant Engraver in 1869 by his father despite no experience or education in die engraving.

While Barber would produce some commemorative coins and medals late in life that were fairly well-received, it is his mediocre earlier work and vindictiveness toward other mint engravers and outside artists that he is remembered for.

Charles Barber's natural hostility toward other artists may have grown in the aftermath of an 1878 competition between him and newly-hired Assistant Engraver George T. Morgan to design a new silver dollar. Mint Director Henry Linderman had recently hired Morgan as an engraver due to his dissatisfaction with the quality of the work by both William and Charles Barber. He rigged the contest for the new silver dollar design by giving Morgan inside information on what he was looking for.

At the end of the day, the person with the highest opinion of Charles Barber's skill was Charles Barber. Most professional sculptors, as well as Directors of the U.S. Mint, had a far lower estimation of his skills—Director of the Mint Edward O. Leech (1889-1893) being a notable exception.

During the American Renaissance in coinage (1907–1921), the common refrain from artists working with the mint was Barber's inept modifications of their designs. Barber placed the ease of striking a coin design over its artistic merits, and often used that as a reason to alter designs from outside artists without their input. When a coin hub made from a design by an outside artist had to have its relief lowered, Barber would apparently simply carve it down, with little to no care on preserving details.

Barber's stock with Theodore Roosevelt, who already considered his coin designs an "atrocious hideousness," fell further with his apparent lack of work ethic. For the President's 1905 inaugural medal, Barber simply changed the date on the 1901 inaugural medal, which itself had been a rush job when Roosevelt was sworn in as president after the assassination of William McKinley.

To be fair, this may have been a case of seriously misplaced priorities on Barber's part, rather than a fit of passive-aggressiveness. The U.S. Mint had contracted to produce coins for several Latin American countries in 1904–1905, and Barber was involved with their designs. Perhaps Barber thought the inaugural medal was of lesser importance that these contracts. If so, it was a grievous mistake.

The 1905 Roosevelt Inaugural Medal

While many popular histories cite 1905 or 1904 as the date when Theodore Roosevelt and Augustus Saint-Gaudens met, the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian states that the two first came to know each other in the 1890s. Roosevelt was an anti-corruption politician in New York City who had yet to emerge onto the national stage, while Saint-Gaudens was already one of America's preeminent sculptors.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens was invited to a diplomatic reception at the White House on January 12, 1905, after President Theodore Roosevelt's reelection. First Lady Edith Roosevelt purposefully assigned Saint-Gaudens sit at the president's table at the exclusive dinner which followed. It was here that conversation between the president and sculptor turned to two subjects: Charles Barber's bland coin designs, and his appalling inaugural medal.

Roosevelt urged Saint-Gaudens to design a replacement medal for his inauguration, but the sculptor was hesitant to accept. He had several active commissions at the time, which were already behind schedule due to his health. Mainly, though, it would mean confronting Barber in his own lair, so to speak, while replacing the inaugural medal he had designed. This was stress that Saint-Gaudens did not need.

Saint-Gaudens acquiesced to Roosevelt's urging at a White House visit on January 16th, under the condition that his former assistant Adolph Weinman would do the physical work on the medal. In a letter to the president dated January 20, 1905, he writes:

"...I have arranged with the man best fit to execute it in this country. He has a most artistic nature, extremely diffident. He would do an admirable thing."

Saint-Gaudens begged the president to keep Weinman's medal away from the U.S. Mint:

"The man there who has charge of the bulk of the ordinary medals already contracted for cannot possibly do an artistic work. He is a commercial medalist with neither the means nor the power to rise above such an average... [O]ur reliefs must be put into other hands and this is to beg you to insist that the work be entrusted to Messrs. Tiffany or Gorham. Otherwise I would not answer for it being botched."

This letter of course cemented Saint-Gaudens as the chief engraver's enemy, with dire results in getting the 1907 double eagle minted.

Weinman worked on the models for the medal in his New York studio, then sent them to Cornish for Saint-Gaudens's approval. After the inevitable requests for changes, Weinman made new models, and the cycle repeated. The March 4th date of Roosevelt's inauguration came and went. The Inaugurational Committee, which was paying for the medal, grew more worried by the week.

In late June, Weinman's models finally received Saint-Gaudens's blessing, and the medals were cast. On July 8, 1905, the president received his gold medal, and a sample of the bronze one. He writes Saint-Gaudens, in part:

"My dear fellow, I am very grateful to you, and I am very proud to have been able to associate you in some way with my administration. I like the medals immensely, but that goes without saying, for the work is eminently characteristic of you. Thank heaven, we have at last some artistic work of permanent worth done for the government!.."

He adds a handwritten postscript:

"I don't want to slop over, but I feel just as if we had suddenly imported a little of Greece of the 5th or 4th centuries BC into America..."

With the saga of the inaugural medal over, Roosevelt was ready for the main event: rejuvenating the nation's coins.

The Struggle Against "Atrocious Hideousness" (Prelude)

The Saint-Gaudens gold eagle and double eagle coins would have never been made without Theodore Roosevelt's intense interest and constant intervention with a recalcitrant U.S. Mint. In his autobiography, Roosevelt summed up the reasons for his crusade:

“In addition certain things were done of which the economic bearing was more remote, but which bore directly on our welfare, because they add to the beauty of living and therefore to the joy of life.

Securing a great artist, Saint-Gaudens, to give us the most beautiful coinage since the decay of Hellenistic Greece was one such act. In this case I had power myself to direct the mint to employ Saint-Gaudens. The first and most beautiful of his coins were issued in the thousands before Congress assembled or could intervene; and a great and permanent improvement was made in the beauty of coinage.”

Roosevelt's first recorded use of the phrase "atrocious hideousness" to describe the coins of the United States was in a letter dated December 27, 1904 to Secretary of the Treasury Leslie Shaw. Having just won the presidency in his own right after completing the term of the assassinated William McKinley, Roosevelt felt he finally had a mandate from the American people. He had put off implementing some of his plans until he had that mandate, and was now ready to move on them. His fight over the nation's currency was one of those projects.

The original copy of what numismatists call "the Genesis Letter" was rediscovered in 2011. It sold in the August 25, 2012 Heritage coin auction for $94,000. The oft-quoted text of the letter is repeated here:

"My dear Secretary Shaw:

I think our coinage is artistically of atrocious hideousness. Would it be possible, without asking the permission of Congress, to employ a man like St. Gaudens to give us a coinage that would have some beauty?

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt

Hon. L.M. Shaw

Secretary of the Treasury"

On verso, a handwritten note in pencil:

"$85,000

Cont fund"

Assumed to be written in Shaw's hand, it is a note that the U.S. Mint's contingency fund stood at $85,000. Saint-Gaudens's fee for designing the coins could be taken from this fund, with no need to ask Congress to appropriate the money.

As chief engraver, Barber would have seen this letter from the President to his superior as a slap in the face. The nickel, dime, quarter, and half dollar were the "atrocious" coins most used in commerce, and all were Barber designs.

Saint-Gaudens demurred when first pressed by Roosevelt to create new designs for the nation's coinage. He later admitted that he was "scared blue" at the thought of spending his last days fighting Charles Barber over what would be the ultimate insult to the vain chief engraver: the first coin in U.S. history that was not designed at the U.S. Mint. It was only after Roosevelt promised to intercede with the mint whenever necessary that Saint-Gaudens agreed to rework the nation's coins.

The Struggle Against "Atrocious Hideousness" (The Designs)

Augustus Saint-Gaudens began his work on the coin designs on an optimistic note, one shared by the president. Neither could have guessed the ordeal ahead in committing Roosevelt's "pet crime."

At the U.S. Mint, Roosevelt's obsession with the new coins was met with bewilderment. No president had ever taken an active interest in the nation's coinage, and neither Mint Director Robert Preston nor Charles Barber knew what to make of the scrutiny bearing down on them from the human hurricane at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Things started innocuously enough, with the mint signing a contract with Saint-Gaudens in July 1905, shortly after Roosevelt's inaugural medal was finished, and the sculptor brainstorming designs.

1908 Saint-Gaudens $20 Obverse

Initially, Saint-Gaudens intended that the $20 double eagle and $10 eagle would share the same design. The front (obverse) would feature a full-length winged Liberty (inspired by the Amor Caritas) striding toward the viewer, a Union Shield in her left hand and the Torch of Enlightenment in her right. The reverse (back) of both coins would have a standing eagle similar to the one on the 1905 inaugural medal. Saint-Gaudens, in describing the concept to Roosevelt, said, "My idea is to make it a living thing and typical of progress."

In November 1905, Roosevelt was the first to raise the stakes in their plan and propose the idea of a very high relief coin:

November 6, 1905

" ...I was looking at some gold coins of Alexander the Great today, and was struck by their high relief. Would it not be well to have our coins in high relief, and also have the rims raised? … What do you think of this?"

Saint-Gaudens was thrilled with his "marching orders":

November 11, 1905

"Dear Mr. President:

You have hit the nail on the head with regard to the coinage. Of course the great coins (and you might almost say the only coins) are the Greek ones you speak of... Nothing would please me more than to make the attempt... but the authorities on modern monetary requirements would, I fear, 'throw fits,'... Perhaps an inquiry from you would not receive the antagonistic reply that would certainly be made to me from those who have the 'say' in such matters."

Shortly afterwards, Roosevelt floated the idea of replacing the traditional Phrygian cap on Liberty with a stylized Native American war bonnet. He wondered to Saint-Gaudens if the public would accept this change. The sculptor supported the idea, telling the president he thought "It should be very handsome."

The most portentous decision made in late 1905 was to remove the motto "In God We Trust" from the coins. Saint-Gaudens was happy to have one less phrase cluttering his design, and Roosevelt considered inscribing the name of the Lord on filthy money to be sacrilege. (The public reaction to this decision is covered in detail in a later section.)

The new year of 1906 found both men in a jovial mood. On January 6th, Roosevelt wrote that he met with his Secretary of the Treasury, Leslie Shaw, regarding his plans to have high profile gold coins struck. In an effort to mollify his boss, Shaw suggested that even if the new gold coins did not stack appropriately, they could still be held in Treasury vaults to back the paper gold certificates in circulation.

"My dear Saint-Gaudens

I have seen Shaw about that coinage and told him it was my pet baby. We will try it anyway, so you go ahead... Of course he thinks I am a mere crack-brained lunatic on the subject, but he said with great kindness there there was always a certain number of gold coins that had to be stored up in vaults, and that there was no earthly objection to having these coins as artistic as the Greeks could desire. (I am paraphrasing his words, of course.)

I think it will seriously increase the mortality among the employes [sic] of the mint at seeing such a desecration, but they will perish in a good cause!"

Saint-Gaudens replied in a similarly jocular tone, while taking a dig at the chief engraver:

"All right, I shall proceed on the lines we have agreed on… I assure you I feel mighty cheeky so to speak... Whatever I produce cannot be worse than the inanities now displayed on our coins and we will at least have made an attempt in the right direction, and serve the country by increasing the mortality at the mint.

There is one gentleman there, however, who, when he sees what is coming may have 'the nervous prostitution' as termed by a native here, but killed, no. He has been in that institution since the foundation of the government and will be found standing in its ruins."

Another bone of contention between the mint and the president was settled that spring. Saint-Gaudens wanted to express the date on the gold coins in Roman numerals. Treasury Secretary Shaw was against the idea, but Roosevelt simply overruled him.

On May 29, 1906, Saint-Gaudens wrote Roosevelt to say the models were nearly done. He was sending his best medallion artist, Henry Hering, to the mint to learn the technical particulars for reducing the models down to coin size. The sculptor apparently had no illusions regarding Charles Barber's reaction to the models:

"The reverse is done… The obverse I am hard at work on. Its completion will not be delayed long and your 'pet crime' as you call it will be perpetrated as far as I am concerned… [I]f you succeed in getting the best of the polite Mr. Barber down there, or the others in charge, you will have done a greater work than putting through the Panama Canal."

Hering took on the actual sculpting of the double eagle models after Saint-Gaudens found it impossible to work more than a few minutes at a time due to his deteriorating health. As Hering finished the first models for the gold coin, Saint-Gaudens began designing the one-cent coin. The sculptor had been hospitalized in February from his colon cancer, and was recuperating in New York in June:

"I am here on the sick list, where I have to remain in the hands of the doctors until the first of August, but my mind is on the coins, which are in good hands at Windsor… Now I am attacking the cent. It may interest you to know that on the 'Liberty' side of the cent I am using a flying eagle, a modification of the device which was used on the cent of 1857... [I] was so impressed by it, that I thought if carried out with some modifications, nothing better could be done."

As the summer of 1906 turned to autumn, Roosevelt became anxious. He wanted to have the coins released to the public before Congress convened on December third. Work on the coins progressed slowly. Unknown to the president, Saint-Gaudens had become completely incapacitated from his cancer that winter.

Roosevelt was nearly beside himself when he writes the sculptor in October:

"... When can we get that design for the twenty-dollar gold piece? … I do not want to bother you, but do let me have it as quickly as possible. I would like to have the coin well on the way to completion by the time Congress meets."

On December 14, 1906, Saint-Gaudens, via Henry Hering, sent plaster models of the gold coins to Roosevelt for his approval. The president was overjoyed:

"Those models are simply immense -- if such a slang way of talking is permissible in reference to giving a modern nation one coinage at least which shall be as good as that of the ancient Greeks… It is simply splendid. I suppose I shall be impeached for it in Congress; but I shall regard that as a very cheap payment!"

Soon after the coin models arrived at the mint in Philadelphia. Mint Director Preston asked the president for his understanding going forward. The mint faced a problem with Saint-Gaudens's high-relief designs that no mint had successfully resolved:

"... [T]he high relief will present difficulties in coinage which have never yet been overcome, and when it comes to that we must ask your patience while we try to work out the problem ... The very best that can be done will be done to give effect to these designs."

Thinking that the gold coin design was done, Saint-Gaudens moved on to the one-cent coin. He intended to replace the tired old "Indian Head" Liberty design with a profile of a classical Liberty. This new design was based on an early study of Victory that Saint-Gaudens sculpted when working on the General Sherman monument. He ultimately went with a different design for Victory's head on the monument, but liked this one so much he had kept it around.

Roosevelt asked Saint-Gaudens to bring back the Indian headdress for the new Liberty, and after consulting with other artists, acquiesced. Later, Saint-Gaudens wrote Roosevelt that he would like to use the new Liberty profile with the headdress on the $20 gold piece as well as the cent.

The profile's lower relief, spread more evenly over the surface of the coin, would make the large double eagle easier to strike. Saint-Gaudens doesn't explicitly say that this was the reason he wanted to use it, and may have been unaware of this technical benefit of switching to the Liberty profile.

Roosevelt wrote Saint-Gaudens in May to say that the relief on the new models was still too high. The mint still found it impossible to strike the double eagle on the coining presses. He suggested that perhaps a new design might be necessary.

Saint-Gaudens replied that his health made it impossible for him to produce a totally new design for the double eagle. He was confident that the relief on the present design could be lowered enough without losing detail in order to be struck on a coining press with one blow.

As Saint-Gaudens's condition continued to worsen, work on the cent was abandoned in favor of getting a gold coin design that the mint could use on a regular coining press. In one of his last letters to Roosevelt, Saint-Gaudens relented on his desire to use the profile design on the double eagle.

May 23, 1907

"Dear Mr. President

...The majority of the people that I show the work to evidently prefer with you the figure of Liberty to the head of Liberty and that I shall not consider any further on the Twenty Dollar gold coin."

The designs were finalized shortly afterward. The $20 gold double eagle would feature the full-length Liberty, sans wings, shield, and Native American war bonnet. The flying eagle would be on the reverse, instead of the standing eagle Saint-Gaudens had previously wanted. The $10 gold eagle would display the profile head of Liberty with the war bonnet, and the standing eagle on reverse. This was the design from the abandoned one-cent coin. Both gold coins had the inscription "E Pluribus Unum" moved to the edge of the coin, with each letter separated by a star.

The Struggle Against "Atrocious Hideousness" (Crossed Signals)

In late 1906, Charles Barber and Assistant Engraver George Morgan teamed up to design a new double eagle pattern. It successfully captured the "French style" that Barber had failed to achieve with his 1892 designs for the silver dime, quarter, and half dollar. The Barber 1906 double eagle pattern is perhaps his best work on a circulation coin. Only one coin was struck, in part to test the mint's new equipment to strike coins with lettered edges.

However attractive this pattern was, the double eagle design train had already left the station, and Teddy Roosevelt was driving it. The president's decision to use Saint-Gaudens's design instead of Barber's only fanned the flames of resentment on the chief engraver's part. His mood was not improved with the headaches caused by Saint-Gaudens's double eagle design failing to strike properly.

Saint-Gaudens's unfamiliarity with the technical requirements of the mint led to problems from the start. Coin and medal designs are made larger than the coins themselves, so that the artists can easily work on the details. These models are then put on a reduction lathe that traces the contours of the model, while engraving it onto the proper size coin die.

The Mint's reduction lathe could only handle models of a maximum diameter of 5-3/8". Saint-Gaudens's medal plasters were usually around twelve inches, and went up to fourteen inches. The reductions would have to be outsourced.

Both Augustus Saint-Gaudens and his brother Louis (also a sculptor) had recently had problems with Tiffany's efforts at reducing their models. Therefore, the initial double eagle models were sent to France in the summer of 1906 to be reduced to the proper size while retaining the details of the original models. This resulted in long periods of waiting for the models and reductions to be shipped back and forth across the Atlantic.

The mint took this opportunity to upgrade their own operations. A Janvier reduction lathe was ordered in October from Dietsche Brothers in New York. This was the latest in medallic technology, and was what the big French engraving houses were using. The lathe, the first Janvier in the United States, arrived in November 1906. Dietsche sent engraving technician Henri Weil to train Barber and Morgan on the new lathe.

Barber had Weil return in February to give them more training. Saint-Gaudens's first set of models were ready to be turned into dies that month. There is some speculation that Barber had Weil, who was an expert on the Janvier, come back to reduce Saint-Gaudens's models and make the coin hubs. That way, when they didn't strike up on the coining press, the problem couldn't be blamed on the reductions.

1908 Saint-Gaudens $20 Reverse

Between February 7th and 14th, 1907, four coins were struck from Saint-Gaudens's first designs. It was impossible to get a full strike on a coining press, regardless how many times it was struck. Even on the heavy-duty medal press, the first strike only transferred half the design. It took a total of six blows to get all the features to show up properly, with a seventh strike to add the letters to the edge. The sans serif lettered collar from the 1906 Barber/Morgan double eagle pattern was used during these test strikes.

Between every strike, the coin had to be removed from the press, heated until it glowed, then dipped in a weak nitric acid solution, so the metal was soft and clean enough. It was then reinserted into the press and struck again.

This was far too time-intensive for the most important gold coin of a thriving nation of 87 million people. All international commerce and large domestic transactions were conducted in gold coin. With a booming economy, the United States was seeing record imports and big business deals. There was no time for a process that took a week to strike two coins.

The reverse die suffered a stress fracture in this first trial run, before the fourth coin could receive the last strike to add letters to the edge. The total for this first test was three complete coins with lettered edge, and the plain edge coin.

As a sign of good faith on the part of the mint, Barber experimented with the original design. Instead of the normal 34 millimeter dies, he cut 27 millimeter dies from Saint-Gaudens's models, to match the diameter of the $10 gold eagle. This would allow the tools for the eagle to be used on the new coin.

He then had the workers make blanks matching the diameter of the eagle, but with the weight of the double eagle. This resulted in a 27 mm blank with twice the amount of gold. With more gold between the obverse and reverse dies, it was easier to fill in the high points on both sides, making the coins easier to strike. The results were very encouraging.

Fifteen of these "checker" double eagles were struck before someone remembered that the Coin Act of September 26, 1890 forbade the mint from changing the diameter of any coin without Congressional approval. Since Roosevelt's orders were to get the coins released into the economy before Congress found out about them, the "checker" idea had to be abandoned.

Neither Saint-Gaudens nor his assistant Henry Hering expected the original ultra-high relief design to strike up on a coin press. This first attempt at striking the double eagle was intended to serve as an experiment to see what the mint's presses were capable of, and to point out areas where the relief could be lowered without the design suffering. Barber knew this and resented the waste of his time.

On February 21st, Saint-Gaudens requested sample coins in various stages of completion, as well as a complete coin. Since this first design was a flop, Barber didn't want to cut a new reverse die just for this, and sent the sculptor some of the incomplete coins he had on hand.

While the numismatic world and most of the public consider the 1907 Ultra High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagle the most beautiful American coin ever made, the sculptor himself wasn't impressed. Upon viewing the completed coin from his unaltered design, Saint-Gaudens remarked: "I am convinced that the die, or hub, is not as successful as it could be."

Saint-Gaudens returned the sample coins in mid-March. The incomplete coins were melted down, and the complete coin was retained by either Mint Director Roberts, or former Mint Director Robert E. Preston. Of these first three complete Ultra High Relief (UHR) coins, the first one went to President Roosevelt, one to Roberts, and the third was presented by Roberts to Preston.

In March, Saint-Gaudens was notified that the extremely high relief of his full-figure Liberty model made it impossible to mint with a single strike of the coining press. A second set of dies with a lowered relief and some minor changes was sent to the mint by Saint-Gaudens in mid-March. Known as the 1907 Very High Relief (VHR) double eagle, the design on these coins were also too high to be struck in the coining presses. There are no known survivors from this die set.

A second run of Ultra High Relief double eagles from the first model were struck between March and April 1907, while the new coin models were being reduced and dies cut. The number of coins struck in this session has been unclear, but has historically been believed to be between thirteen and fifteen.

Ultra High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles were struck for the third and last time on December 31, 1907. New Mint Director Frank Leach (not to be confused with Edward Leech) wanted one for himself, one for the Treasury Secretary, and one for Saint-Gaudens's widow. Barber accordingly struck three coins. The law stipulated that all coin dies displaying a date must be destroyed after December 31st of that year. Accordingly, the Saint-Gaudens obverse dies were destroyed on January 2nd.

Unfortunately, President Roosevelt decided that he would like another Ultra High Relief double eagle after the dies were destroyed. Therefore, the coin earmarked for the Saint-Gaudens estate was given to the president.

Word had leaked out to Mrs. Saint-Gaudens that the Mint was making a UHR double eagle for her, despite orders from Leach to keep the idea secret. Since the last UHR die had been destroyed, this led to some awkwardness.

Roosevelt caught wind of the situation, and threatened to force Barber to engrave a special 1908-date Ultra High Relief die just to strike a coin for the Saint-Gaudens family. Leach was able to dissuade the president from such drastic action, suggesting that one of the two UHR coins in the mint collection be given to the family.

HOW MANY 1907 ULTRA HIGH RELIEFS WERE STRUCK?

Some guesswork has been required when trying to pinpoint exactly how many 1907 Ultra High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles were minted. It is generally thought that 19 or 20 coins have survived to the present day (eight of those were purchased by Charles Barber for his own collection, including the unique Plain Edge with the reverse die crack). Mint Director Frank Leach recalls in his memoirs that 19 were struck.

It is known that there were three, plus the Plain Edge coin, struck between February 7th and the 14th. These went to Roosevelt, Preston, and Roberts. There were three struck on December 31st, which went to Roosevelt, Leach, and Treasury Secretary Cortelyou. Two from the second run in March and April went into the mint coin collection. One of these was later given to Mrs. Saint-Gaudens. Seven from this same run were purchased by Barber.

However, a February 5, 1908 Mint report to the Treasury Secretary states that 13 Ultra High Relief double eagles were struck in 1907. Since the number of surviving UHR coins is larger than that, it may be that this document was only reporting the number of coins struck in the middle of the year. Accepting that the second run of 1907 UHR double eagles was 13 coins, the total of 19 coins (20 if the Plain Edge is counted) matches the most common estimate of survivors.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens died from complications from colon cancer on August 3, 1907. On August 7th, an angry Roosevelt wrote to the mint: "There must be no further delays. Let the two coins [eagle and double eagle] be finished and put into circulation at once; by September first."

Hering sent a third and final set of models with even lower relief to the mint in later that month.. Known as High Relief, they still took three strikes from the medal press to complete. After this failure, Roosevelt came to the conclusion that the Mint (Barber) was sabotaging production of Saint-Gaudens's double eagle.

This is the situation when Frank Leach stepped into the middle of the conflict. Leach arrived in Washington D.C. from San Francisco in the first week of October. The president soon summoned him to the White House. In his autobiography, Recollections of a Newspaperman:

"Before I had become familiar with my surroundings, the President sent for me. In the interview that followed he told me what he wanted, and what the failures and his disappointments had been, and proceeded to advise me as to what I should do to accomplish the purpose determined upon in the way of the new coinage. In this talk, he suggested some details of action of a drastic character for my guidance, which he was positive were necessary to be adopted before success could be had."

It is possible that Roosevelt's "drastic" suggestion was to fire Barber and hire a new chief engraver. Leach convinced the president that, as he had only just arrived in Washington, he had had no time to travel to Philadelphia and investigate the problem. Until then, he could not propose a solution. "All you want, Mr. President," he said, "is the production of the coin with the new design, is it not?" When Roosevelt agreed, Leach told him, "Well, that I promise you."

Leach ordered the mint to begin production of the High Relief double eagles immediately, despite the fact that it took 12 minutes and three strikes on the medal press to mint each coin. As the Mint began production of the coins, Chief Engraver Barber wrote to Philadelphia Mint Superintendent John Landis, in part:

"Mr Hart has put the mill into operation and I send you two pieces showing the result, these are not selected as all the coins now made are the same as these two, which gives me alarm, as they are so well made that I fear the President may demand the continuance of this particular coin."

Leach fulfilled his promise to the President when he laid these two brilliantly struck high relief coins on his desk, just a few days after their first meeting. Thrilled with the coins and Leach's prompt success with the mint, Roosevelt set another task for the new Mint Director: Produce enough High Relief double eagles for a nationwide distribution of the coins, and do it in thirty days. The fact that it took three strikes on a medal press to mint each coin did not phase him. By running the medal presses night and day, the mint struck 12,637 High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles by the deadline.

Production difficulties at the start of this run at the mint resulted in what is called the High Relief Wire Rim Saint-Gaudens double eagle. The high pressures exerted by the medal presses caused a thin ring of gold to be squeezed into a tiny gap between the die and the collar. This resulted in a very thin "fin" around the rim of the coin. Not only did this prevent the coins from stacking properly, the coin became underweight when pieces of the fin broke off.

Barber corrected the error early in production. The remaining coins are called Flat Rim High Relief. These were the first Saint-Gaudens double eagles released to the public, and demand was overwhelming. The Boston sub-treasury had received 500 High Relief double eagles, and was sold out within hours. Scalpers were demanding $30 or more per coin on the resale market, while the entire mintage of High Relief coins quickly disappeared as souvenirs.

It was up to Barber to flatten the relief on this third double eagle model far enough to allow the mint to produce the coins on the regular coining presses with a single blow. Still unfamiliar with the Janvier reducing machine, his efforts washed out a great deal of the coin's detail. While he attempted to restore some of the details on the hub by hand, even well-struck samples of these low relief coins look weak. These were the first Saint-Gaudens double eagles to carry the date in Arabic numerals. These coins are known as "Saints" to help differentiate these coins from the high relief version with Roman numerals.

The difference in daily production between the high relief and low relief coins show the necessity of having a design that will strike on a coining press. 12,367 High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles were produced in one month, by running the medal presses 24 hours a day. Barber's low relief "Saint" version began distribution to the public on December 13, 1907. By the end of the year, 361,667 low relief double eagles had been produced

Even though the ordeal of getting the Saint-Gaudens double eagle into production was doubtlessly Barber's worst year and a half as chief engraver, he was not blind to the artistic merit of the coin. After his death, his impressive collection of rare coins was found to include eight Ultra High Relief 1907 Saint-Gaudens double eagles, including the unique Plain Edge from the first four struck.

Saint-Gaudens $10 Eagle

The Saint-Gaudens Liberty Head eagle faced a relatively tranquil beginning, compared to the double eagle.

Production using Saint-Gaudens's first model began late in August 1907. 500 high relief coins were struck on medal presses by early September. Similar to the High Relief double eagle, "collar slop" allowed wire rims to form during the minting process due to the high pressure of the medal press. Another 42 were struck from late September to December, possibly to troubleshoot the problems causing the wire rims.

The practically non-existent rims left the features of the coin unprotected. This not only resulted in wear to the features, but meant that it was impossible to stack the coins. The uneven features touched when these coins was placed atop another, making them wobble

The Wire Rim Saint-Gaudens eagles were never released to the public, for obvious reasons. Instead, they were given out as favors to politically well-connected people, and purchased directly from the Treasury by numismatists. Amazingly, 70 of these coins remained unsold for nine years, and were melted down in 1915.

The wire rims were not the only problem with this initial run of Saint-Gaudens eagles. Barber's inexperience with the Janvier reduction lathe caused these coins to have the same problems with lost details and a "mushy" appearance that the low relief double eagles faced. Philadelphia Mint Superintendent Landis was frank in his appraisal of Barber's results: "it just seems to take the life out of it."

The lack of rims on this first version, as well as the need to strike the coins on a medal press, meant that the design had to be changed.

Barber slightly lowered the relief on the coin, and added a raised rim. This combination allowed the coins to stack properly. This version also suffered from washed-out details due to Barber's lack of skill on the new reducing lathe.

Barber considered the new design a success. It stacked correctly, and more importantly, could be struck on the high-speed coining presses. He ordered full production to begin after the changes were approved by Treasury Secretary Cortelyou and President Roosevelt.

Naturally, Henry Hering was appalled when he saw the coin. Aided by Homer Saint-Gaudens, the late sculptor's son, Hering designed a new model that both corrected the failures in the original design, and cured the ills of Barber's "improvements." To differentiate the new design, he removed the triangular periods on either side of the motto "E Pluribus Unum" inscribed on the reverse of the coin. The new models arrived at the mint in mid-September.

Mint Supervisor Landis, who had not shared Barber's enthusiasm over the Rolled Edge design, now had an alternative to present his superiors. Sending one each of the Rolled Edge eagle and the new "No Periods" eagle to Mint Director Leach, he wrote:

"You will notice that the eagle from the last model is a great improvement over those of the first model [the Rolled Edge was based on Saint-Gaudens's first model]. The latter are indefinite in detail and outline, not being at all sharp and look like imperfect coins or coins that have been sweated¹, while the former is sharp in outline, the detail shows up well, the border is broad and prominent, and the coins will stack perfectly."

¹"sweating" a coin is deliberately wearing it down in order to collect the resulting gold dust

Since 315,000 Rolled Edge eagles had already been made, Landis made a bold suggestion:

"... I would strongly urge upon you the expediency of immediately replacing the $315,000 now on hand…. I think we will be severely criticized, and certainly deserve to be, if the eagles already struck should be allowed to go into circulation."

Seeing the two designs side by side demonstrated the unquestionable superiority of the third design. All but fifty of the 31,500 Rolled Edge eagles were promptly melted. The fifty held back were distributed to museums and public coin collections, per President Roosevelt's orders.

The dies of the No Periods eagle prepared by Barber retained most of the details of the plaster models, with only a slight weakness on the high parts of either side: the hair curls on the Liberty profile, and the highest parts of the eagle's left/top wing. 239,406 1907 No Period Saint-Gaudens eagle were produced.

The Struggle Against "Atrocious Hideousness" (Finale)

Today, the Saint-Gaudens double eagle is generally hailed as the finest coin ever produced by the United States. Opinions of the coin were not so unanimous in 1907, however.

Some panned the reverse on the $20 for being a copy of the Longacre 1857 Flying Eagle "white cent." This was actually a valid observation: Saint-Gaudens had admired that design as a kid growing up on the Lower East Side in New York. Others complained that the eagle was trailing his talons instead of having them properly tucked against his body. When Mint Director Leach mentioned this to Roosevelt, the president disagreed. When Leach still expressed doubt (not knowing Roosevelt's reputation as a ardent outdoorsman), he was sent to a nearby aviary to see for himself. It only took a few minutes for the director to see the president was right.

Somehow, a rumor started that the profile of Liberty on the $10 eagle was that of an Irish barmaid named Mary Cunningham, who lived in the next town over from Saint-Gaudens's studio in Cornish, New Hampshire. Anti-immigrant portions of the population were outraged, proclaiming that only the image of a "pure American" should be on the coins of the United States. Homer Saint-Gaudens later wrote of his amusement over the ruckus:

"As a matter of fact, the features of the Irish girl appear only at the size of a pin-head upon the full-length Liberty, the body of which was posed for by a Swede, while the profile head, to which exception was taken, was modeled from a woman supposed to have negro blood in her veins. Who, other than an Indian, may be a 'pure American' is undetermined. In reality here, as in all examples of my father's ideal sculpture, little or no resemblance can be traced to any model; since he was always quick to reject the least taint of what he called 'personality' in such instances."

Others complained about the Native American war bonnet the Liberty wore on the eagle, noting that females did not wear feather headdresses. Roosevelt, who had insisted on its inclusion, saw it as no more unrealistic as the Phrygian cap traditionally shown on images of Liberty, as such caps had never been worn in America.

Saint-Gaudens designed the $10 gold eagle (above) and the $20 gold double eagle.

In a later meeting at the White House, Director Leach told Roosevelt that the U.S. Mint had not only surpassed the best any mint had ever done, it had outdone even the best coins of the ancient Greeks. Leach noted that the Greeks had produced high reliefs on one side only of their coins, while the new Saint-Gaudens coins had high relief features on both sides.

It was now the president's turn to play Doubting Thomas. He ordered a secretary to retrieve an Alexander the Great gold coin from his study. When the coin was dutifully presented, Roosevelt saw that his Mint Director was right.

The ugliest, most widespread criticism of the new coins, however, was the absence of the phrase "In God We Trust."

"In God We Trust"

Religious fervor, much of it rooted in the abolitionist movement, ran high in the Northern states during the Civil War. The fact that the nation, according to most of these people, was on a holy crusade to end slavery only heightened the usual "God is on our side" sentiment seen in times of war. This led to a movement to have God's name on America's coins, to bind the nation to the Lord.

As one of the duties of the Treasury Department is overseeing the minting of the nation's coins, Secretary Salmon P. Chase was the target of much of these efforts. The first known appeal of this type to Chase was penned by a Pennsylvania clergyman named W.R. Watkinson, dated November 13, 1861. It read, in part:

"One fact touching our currency has hitherto been seriously overlooked. I mean the recognitions of the Almighty God in some form on our coins.

You are probably a Christian. What if our Republic were not shattered beyond reconstruction? Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?... "

This struck a sympathetic chord with Chase, a long-time abolitionist. Chase had offered pro bono representation in court for escaped slaves before the war, and helped form the anti-slavery Republican Party. Only a week after receiving the Rev. Watkinson's appeal, Chase instructed the U.S. Mint to start work on a motto referring to God to be placed on America's currency:

"Dear Sir: No nation can be strong except in the strength of God, or safe except in His defense. The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins.... You will cause a device to be prepared without unnecessary delay with a motto expressing in the fewest and tersest words possible this national recognition."

In 1864, Congress authorized a two-cent coin, which would be the first to bear the motto "In God We Trust." By 1866, the motto appeared on every coin large enough to contain it. There the issue rested, until 1905.

Early in the design process for the eagle and double eagle, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and President Theodore Roosevelt decided not to include "In God We Trust" on either coin.

Both the president and the sculptor preferred not to include the motto, for different reasons. For Saint-Gaudens, it meant being forced to crowd together some features of his preliminary designs in order to fit the four words. For Roosevelt, its inclusion had the effect of cheapening the name of the Almighty.

This decision to omit the motto was based on a loophole in the Coinage Act of 1873 that had gone unnoticed for thirty years. In Section 18 of the Act, the next-to-last clause states:

"...and the director of the mint, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, may cause the motto 'In God We Trust' to be inscribed upon such coins as shall admit of such motto;"

The word "may" in this clause gave the president room to omit the motto. In legal use, "may" gives a party the choice of whether or not to act, while "shall" is an order. In this case, coin designs shall (must) include the word Liberty, the motto E Pluribus Unum, the year, and the denomination (among other things). They "may" include In God We Trust, if the Secretary of the Treasury so decides. Therefore, the inscription was omitted from the designs.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens lost his long, agonizing fight against colon cancer at his home in Cornish, New Hampshire on August 3,1907, before the coins were released. This meant he was spared the fire and fury over the decision to remove the motto.

Roosevelt's response to the national uproar over his decision can be described in a nutshell from the subheadings in a New York Times article dated November 14, 1907:

"President Says Such a Motto on Coin Is Irreverence, Close to Sacrilege"; "No Law Commands Its Use"; "He Trusts Congress Will Not Direct Him to Replace the Exalted Phrase That Invited Constant Levity."

Roosevelt's letter to the public was reprinted in its entirety by the Times. In it, he explains his commonly-known objection to the motto being included on coins: "My own feeling in the matter is due to my very firm conviction that to put such a motto on coins, or to use it in any kindred manner, not only does no good, but does positive harm, and is in effect irreverence, which comes dangerously close to sacrilege."

Another objection to having the name of God on the instruments of Mammon was the ridicule that had been heaped on the motto:

"In all my life I have never heard any human being speak reverently of this motto on the coins or to show any signs of it having appealed to any high emotion in him, but I have literally, hundreds of times, heard it used as an occasion of and incitement to the sneering ridicule which is, above all things, undesirable that so beautiful and exalted a phrase should excite.

For example, throughout the long contest extending over several decades on the free coinage question, the existence of this motto on the coins was a constant source of jest and ridicule, and this was unavoidable. Every one must remember the innumerable cartoons and articles based on phrases like 'In God we trust for the 8 cents,' 'In God we trust for the short weight,' 'In God we trust for the 37 cents we do not pay,' and so forth and so forth.

Surely, I am well within bounds when I say that a use of the phrase which invites constant levity of this type is most undesirable. If Congress alters the law and directs me to replace on the coins the sentence in question, the direction will be immediately put into effect, but I very earnestly trust that the religious sentiment of the country, the spirit of reverence in the country, will prevent any such action being taken."

In 1908, Congress did just that, ordering the restoration of the motto on the two gold coins.

Saint-Gaudens's Numismatic Legacy

The upheaval in U.S.numismatics set in motion by the sheer will of Theodore Roosevelt and the unparalleled skill of Augustus Saint-Gaudens was only the beginning. Over the next 14 years, Chief Engraver Charles Barber and Assistant Engraver George Morgan would be passed over eight more times in favor of designs created by professional sculptors.

This American Renaissance of coins was completed in December 1921, when Anthony de Francisci's Peace Dollar replaced the 1878 Morgan dollar design. Every U.S. coin denomination now had a dynamic new look created by some of America's most talented sculptors.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens's legacy ran through these designs. From the Buffalo nickel to the intaglio Indian Head half eagle, these artists had either worked directly with the master sculptor or had trained under some of his most famous students. Only Victor D. Brenner, designer of the 1909 Lincoln cent, did not have a connection to Saint-Gaudens.

Another interesting fact of the American Renaissance of the nation's coins was that, for the first time in history, a common design was not used for all gold coins or all silver coins. Of the four gold coins (quarter eagle, half eagle, eagle, and double eagle), only the half and quarter eagle shared a design. Each of the nation's silver coins (dime, quarter, half dollar, and silver dollar) had totally separate designs.

The self-important Charles Barber not only suffered the indignity of seeing his designs cast aside at the earliest opportunity, he was forced to strike the coins that were replacing them. He seems to have taken his frustrations out by not using the greatest care in "modifying" the designs before production, either over the protests of the artists, or without their knowledge.

CHRONOLOGY OF COINS OF THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE

1907 - Saint-Gaudens's double eagle and eagle coins are posthumously released, after numerous difficulties between Saint-Gaudens and his assistant Henry Hering on one side, and Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint Charles Barber on the other.

1908 - Saint-Gauden protege Bela Lyon Pratt is commissioned to redesign the remaining two circulating gold coins, the five-dollar half eagle, and the two-and-half-dollar quarter eagle. His controversial intaglio Indian Head design was the first US coin to feature a realistic Native American. Like his mentor, Pratt was forced to petition President Theodore Roosevelt to intervene with Charles Barber, whose complaints and foot-dragging meant that the coins were not released until October. The sloppy die cutting and Barber's modifications let Pratt to decry him as a "butcher or blacksmith."

1913 - Barber's "V nickel" design (perhaps his best design) was replaced by the "Buffalo" nickel design of famed Western sculptor and former Saint-Gaudens assistant James Earle Fraser. Once again, Charles Barber had been cut completely out of the design process. However, it was notable that Barber sided with Fraser when a vending machine company continuously demanded changes to the design. Fraser's realistic Indian Head was a composite of at least three subjects. Like Saint-Gaudens, Fraser insured that his allegorical figures did not portray one single person.

Fraser's nickel exhibited some of the same problems as Hermon MacNeil's Standing Liberty quarter would have three years later: on both coins, the date was struck on one of the highest points on the coin, where it was unprotected by the rim. This resulted in the dates quickly wearing away, necessitating a design change to lower that part of the coins.

1916 - The three silver Barber coins were up for renewal in 1916. It was this vilified common design of the dime, quarter and half dollar that Theodore Roosevelt had in mind when he declared the nation's coins an "atrocious hideousness." For obvious reasons, Barber was not consulted regarding new designs. Instead, the Treasury Department held a three-artist invitational competition that resulted in Adolph A. Weinman winning the commission for both his "Mercury" dime, and "Walking Liberty" half dollar, and Hermon MacNeil that of the Standing Liberty quarter.

The third sculptor, Albin Polasek, was a new face in the American art scene, but already exhibited great talent. Had he not been competing against Weinman, he could very well have won one of these commissions. The Czech-born sculptor went on to become celebrated in his adopted land, including a long career as an instructor later in life.

Weinman was one of Saint-Gaudens most talented assistants who, as noted earlier, designed the 1905 Theodore Roosevelt inaugural medal. He later worked with other famous sculptors such as Daniel Chester French, and Saint-Gaudens's friend and Beaux-Arts classmate Olin Warner. Weinman opened his own studio in 1904.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens considered Hermon MacNeil in the vanguard of the next generation of American sculptors, and took great interest in his career. When MacNeil returned in 1890 from his studies in Paris, he asked Saint-Gaudens for a letter of recommendation to present to Philip Martiny. Martiny had been one of Saint-Gaudens's assistants on his Shaw Memorial and The Puritan, and was now involved with the architectural sculptures at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. MacNeil also worked with another of Saint-Gaudens's famous assistants at the World's Far, Frederick MacMonnies.

In 1895, MacNeil was awarded the three-year Rinehart Scholarship to the American Academy in Rome by a panel of four judges, including Saint-Gaudens. Some of MacNeil's work prior to winning the commission for the Standing Liberty quarter included his celebrated Native American sculpture "The Sun Vow" and the medal for the 1901 Pan American Expo.

1921 - The final coin to be redesigned the American Renaissance era was Anthony de Francisci's Peace Dollar. He had no direct connection with Saint-Gaudens, but had been thoroughly immersed in his style. Francisci had been taught by or assisted no fewer than four famous sculptors who had learned their trade under the master: James Earle Fraser, Adolph Weinman, Philip Martiny, and Hermon MacNeil.

The U.S. Mint held an invitational contest in the last week of November 1921 to design a new silver dollar emblematic with peace to mark the end of World War One. The sculptors invited in addition to de Francisci were Robert Aitken, Chester Beach, Victor D. Brenner, John Flanagan, Henry Hering, Hermon MacNeil, and Robert Tait McKenzie.

The Mint gave the eight chosen artists a mere three weeks to submit bas-reliefs of their completed designs, with the aim of starting production of the new dollar before the end of the year. Francisci, by far the youngest and least experienced competitor, was announced the unanimous winner on December 19th.

Due to the nearly impossible deadline the artists had been given to make their designs, some shortcuts were absolutely necessary. According to numismatic expert R.W. Julian in Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States (ed. Q. David Bowers), de Francisci used Saint-Gaudens's obverse on the 1907 gold eagle for his basic composition, as well as "certain other works by the same artist."

As there was no time to contract a professional model, de Francisci used his wife Teresa as a stand-in. Contrary to the popular rumor of the time, the final model is not a portrait of Teresa. It is a composition of Teresa's face, the profile from Saint-Gaudens's 1905 gold eagle, and de Francisci's stylization of the results to present an allegorical image of Liberty that was not a depiction of an actual person.

THE COINS OF THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE

| Year | Denomination | Designer |

|---|---|---|

| 1907 | $20 Double Eagle | Augustus Saint-Gaudens |

| 1907 | $10 Eagle | Augustus Saint-Gaudens |

| 1907 | $2.50 Quarter Eagle | Bela Lyon Pratt |

| 1908 | $5 Half Eagle | Bela Lyon Pratt |

| 1909 | 1¢ Lincoln Cent | Victor D. Brenner |

| 1913 | 5¢ Buffalo Nickel | James Earle Fraser |

| 1916 | 50¢ Walking Liberty Half Dollar | Adolph A. Weinman |

| 1916 | 25¢ Standing Liberty Quarter | Hermon MacNeil |

| 1916 | 10¢ "Mercury" Dime | Adolph A. Weinman |

| 1921 | $1 Peace Dollar | Anthony de Francisci |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Calvin, Ruth Mehrtens. "Saint-Gaudens." American Heritage Magazine. July/July 1985: vol. 36 issue 4.

Carnegie Institute. Catalogue of a Memorial Exhibition of the Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens Carnegie Institute, April Twenty-Ninth Through June Thirtieth,

Nineteen Hundred And Nine. Pittsburgh: 1909.

Chaffee, Richard. "Richardson's Record at the École des Beaux-Arts." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. vol. 36 no.3 October 1977: 175.

Cooper Union Alumni Association. "Augustus Saint-Gaudens Award Winners." <http://cooperalumni.org/about/hall-of-fame/augustus-saint-gaudens-award-

winners-2>

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. New York: Knopf Doubleday Press, 2007: 198–199.

Dryhout, John H. The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. University Press of New England, 1982 (2008 ed.): 33–36.

Fricker, Donna and Jonathan. "The Beaux-Arts Style." Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation, 2010.

Hagedorn, Hermann, ed. The Works of Theodore Roosevelt. New York. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1923–1926.

Halperin, James et al. The Coinage of Augustus Saint-Gaudens: as illustrated by the Phillip H. Morse Collection. Dallas, TX. Ivy Press. 2006.

Heineman, Ben W. Jr. "The Sculptor Who Brought Dead Civil War Heroes to Life." The Atlantic Magazine. May 25, 2012.

Heritage Auctions. "1907 Ultra High Relief Twenty Dollar, PR68 Ex: Saint-Gaudens Estate." Lot #4412, 2015 January 5–12 FUN U.S. Coins Signature Auction -

Orlando #1216. <https://coins.ha.com/itm/proof-high-relief-double-eagles/1907-ultra-high-relief-20-inverted-edge-letters-asg-on-edge-pr68-by-both-ngc-and-pcgs-secure/a/1216-4412.s>

Heritage Auctions. "Letter of President Theodore Roosevelt to Secretary of the Treasury Leslie M. Shaw." Lot #5433, 2012 August 2–5 U.S. Coins Signature

Auction - Philadelphia #1173. <https://coins.ha.com/itm/high-relief-double-eagles/double-eagles/letter-of-president-theodore-roosevelt-to-secretary-of-the-treasury-leslie-m-shaw-dec-27-1904/a/1173-5433.s>

Julian, R.W. "Historical Background: Peace Silver Dollars 1921–1964." Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia vol. 2.

Bowers, Q. David, ed. Irvine, California. Bowers and Morena Galleries. 1993: chapter 16.

Leach, Frank A. RECOLLECTIONS OF A NEWSPAPER MAN – A Record of Life and Events in California. Samuel Levinson, 1917.

Moran, Michael F. "A Medal for Edith." Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal vol. XXIX, no. 4. Fall 2008: 5–13.

New York Times, The. "Roosevelt Dropped 'In God We Trust'." The New York Times. November 14, 1907.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer, ed. "Roosevelt and Our Coin Designs: Letters Between Theodore Roosevelt and Augustus Saint-Gaudens." The Century Magazine.

April 1920, vol. 99 no. 6: 721–736.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer, ed. The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. vol. 1, vol. 2. New York: Century Co., 1913.

"Shaw Memorial." National Gallery of Art. <https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.102494.html>

WNET (PBS). "About Augustus Saint-Gaudens." American Masters. December 13, 2000. <http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/augustus-saint-gaudens-

about-augustus-saint-gaudens/695/>

Steven Cochran

A published writer, Steven's coverage of precious metals goes beyond the daily news to explain how ancillary factors affect the market.

Steven specializes in market analysis with an emphasis on stocks, corporate bonds, and government debt.